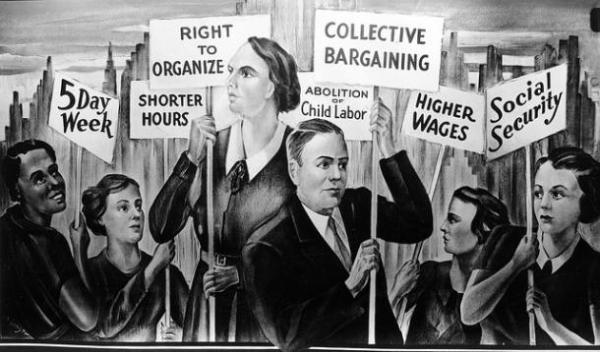

This scene from the 1969 film, Burn! is certainly thought-provoking. However, it operates under – as this blog will argue – a defunct paradigm. It has been replaced by one more ruthlessly efficient and fantastical! It is they hyperreal component of our contemporary society-economy. This is the third blog in a row on the topic of hyperreality – and it will be the last (for a while, at least) – but this particular situation is not only fascinating but relevant for us all.

But first things first: definitions.

Work. Work, in economic-productive terms (i.e., what you do at a job), is defined by the OED as a particular act or piece of labour; a task, job.

Labour, by the same meaning, is similarly defined as physical exertion [can be and often is mental in contemporary society] directed to the supply of the material wants of the community; the specific service rendered to production by the labourer or artisan.

Job is defined as a piece of work; especially a small definite piece of work done in the way of one’s special occupation or profession.

But work, in this context, and in the context of our contemporary society – one in which mass material production as the basis of the economy is largely obsolete, replaced by services and other intangibles as the new consumables, and all this being facilitated by a global network of mass communications systems – takes on a new and terrifying meaning. Crimethinc’s most recent publication, Work, gets into the specifics of what work used to be, what it has become, and what we can do about it. For them, work is the leasing of one’s creative powers to others. They continue:

Selling our time rather than doing things for their own sake, we come to evaluate our lives on the basis of how much we can get in exchange for them, not what we get out of them. As freelance slaves hawking our lives hour by hour, we think of ourselves as each having a price; the amount of the price becomes our measure of value. In that sense, we become commodities, just like toothpaste and toilet paper. What once was a human being is now an employee, in the same way that what once was a pig is now a pork chop. Our lives disappear, spent like the money for which we trade them.

But it isn’t just the person that is transformed from human into commodity, but the socioeconomic system as well. Guy Debord wrote, in Society of the Spectacle, of what likely preceded such a personal transmutation:

When economic necessity is replaced by the necessity for boundless economic development, the satisfaction of primary human needs is replaced by an uninterrupted fabrication of psuedo-needs which are reduced to the single psuedo-need of maintaining the reign of the autonomous economy.

We, especially as Westerners see this all around us, every day. The sacred importance of the economy is as ubiquitous as the priests of the economy – CEOs, economists, politicians, and laymen alike – seeking to construct endless GDP as surely as the Babylonians sought the heights of omnipotence. These caste-members give pronouncements as if they were oracles: lower interest rates!; reduces taxes on the most profitable!; disempower labor unions!; cut domestic aid programs!; open up foreign markets!; privatize!!: as if the economy were a fickle god, whimsically bestowing upon its subjects profit or poverty depending on the value of their prostrations. The economy has become the God of the West (and Jesus admonished us: Matthew 6:24), and we serve it now (not the other way around).

But this is not the end of the analysis. For Baudrillard infuses the chimerical into work:

The whole world still produces, and increasingly, but subtly work has become something else: a need (as Marx ideally envisioned it but not in the same sense), the object of the social “demand,” like leisure, to which it is equivalent in the course of everyday life. A demand exactly proportional to the loss of a stake in the work process… :the scenario for work is there to conceal that the real of work, the real of production, has disappeared. And the real of strike as well…

So… Our work is not really our own; it is not even meaningful in a social sense since it no longer truly serves us; and as a result, the work we do has become a farce of the process of human being. But what if one of us were to find happiness and meaning in our work – could we somehow contradict this conclusion? It doesn’t seem likely. For it amounts to a Sisyphean feat: eternally pushing the boulder up the hill, only to have it roll back down again and again (And Camus argued that we can – we must! – find happiness in this).

I think he’s right: it is possible for a slave to love his condition, but then again: a slave isn’t a subject, but an object; not a person, but a commodity.